Fogg Behavior Model

Prompts tell people to "do it now!"

The third element of the Fogg Behavior Model is Prompts. Without a Prompt, the target behavior will not happen. Sometimes a Prompt can be external, like an alarm sounding. Other times, the Prompt can come from our daily routine: Walking through the kitchen may trigger us to open the fridge.

The concept of Prompt has different names: cue, trigger, call to action, request, and so on.

(I once called this element the “Trigger.” I changed this term in late 2017. Now I use “Prompt.”)

Examples of Prompts

Facebook uses Prompts effectively to achieve their target behaviors.

Here’s one example: I hadn’t used my “BJ-Demo” Facebook account in a while, so Facebook automatically sent me this Prompt to achieve their target behavior: Sign into Facebook. I’ve posted a screenshot of the email below.

Note how this specific behavior — signing in — is the first step of Facebook’s larger goal: reinvolve me in Facebook. (What the system doesn’t know is that I’m already super involved using Facebook with my real account. My demo account is for teaching only.)

Three Types of Prompts

The Fogg Behavior Model names three types of Prompts: Facilitator, Signal, and Spark. Those designing to influence behavior should use the Prompt type that matches their target user’s context, which combines Motivation and Ability.

Look at the Facebook example above. What type is it? As I see it, this message from Facebook is mostly a Facilitator. The green “sign in” button is super prominent, making it easy for me to click and perform the target behavior. In addition to the green button, the Prompt message provides three other links that take me to Facebook.

Prompts can lead to a chain of desired behaviors

Prompts might seem simple on the surface, but they can be powerful in their simplicity (that’s the definition of elegance). An effective Prompt for a small behavior can lead people to perform harder behaviors. For example, if I can prompt someone to walk for 10 minutes a day, that person may then buy some walking shoes without any external triggering or intervention. That’s elegant influence because the walker doesn’t feel like she’s being compelled to buy shoes. It’s a natural chain of events that an effective Prompt puts into motion.

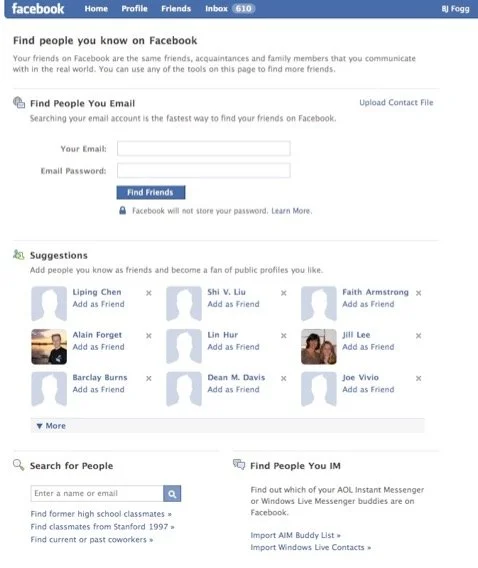

Note how this behavior chain works in the Facebook example above. This uncluttered Prompt from Facebook offers me four ways to click and log into Facebook. In any of the four cases, the link takes users to a specific page on Facebook, called “Find people you know on Facebook.” That’s smart! Instead of just logging inactive users into the main page, the Facebook Prompt takes people to a page where they can find more friends.

So the behavior chain to reinvolve users in Facebook looks like this:

Get users to log in (the email does this)

Get user to link to more friends (the “Find people” page does this)

Trust that new friends will respond to inactive user (a natural result of friending people)

Trust that inactive user will respond to friends and get more involved with Facebook (again, a natural reaction)

Note how these steps move inactive users toward Facebook’s bigger goal — making Facebook a daily habit, a ritual, and perhaps an obsession.

Also note how the initial Prompt from Facebook did not say “connect to more friends – click here!” That would seem like a complicated behavior to novice users. That would have been like asking a sedentary person to buy walking shoes. The smart designer asks people to do simple things — walk for 10 minutes, click here. Once achieved, the simple behavior then opens the door to harder behaviors: buy walking shoes, connect to more friends.

Many designers make the mistake of asking people to perform a complicated behavior. A corresponding mistake is packing too much into a Prompt. Neither path works well. Simplicity changes behavior.

Below is a screenshot of Step #2 in Facebook’s “Reinvolvement” Behavior Chain. The Prompt — [sign into Facebook] — opens the door to the more complicated behavior of adding friends.

Facebook has figured out many ways to prompt a simple behavior than then leads to other behaviors. No one uses Prompt better than Facebook. This is why Facebook has become a major force in the world.

The takeaway message for designers is to map out the behavior chains you need — the user flow you want to happen. (You will likely have more than one.) Then figure out how to get people to do the first behavior in a chain. If people don’t naturally take the next step in the chain, then figure out how to get the next step to happen. Step by step. Continue this process, until the chain works.